I recently posted about what placemaking means and the Valuing Creative Placemaking research project that I initiated with a team of great academics, commissioned by Landcom / UrbanGrowth NSW. The crux of our research project into creative placemaking is how it impacts the people who use our streets, town centres and city spaces. Importantly, we are looking how one might measure the economic social and environmental impact of creative placemaking. And even just mentioning that goal is a hot topic.

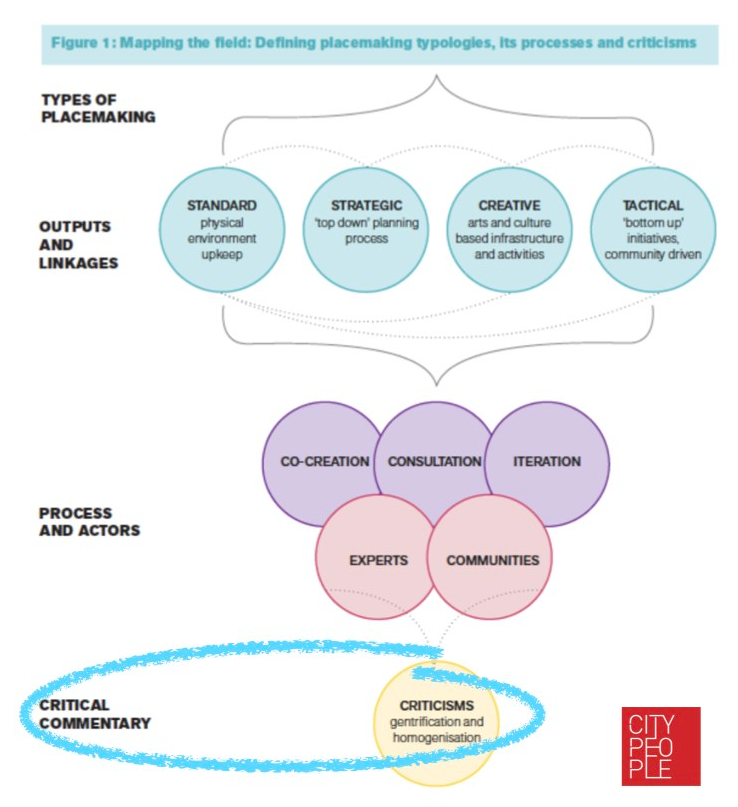

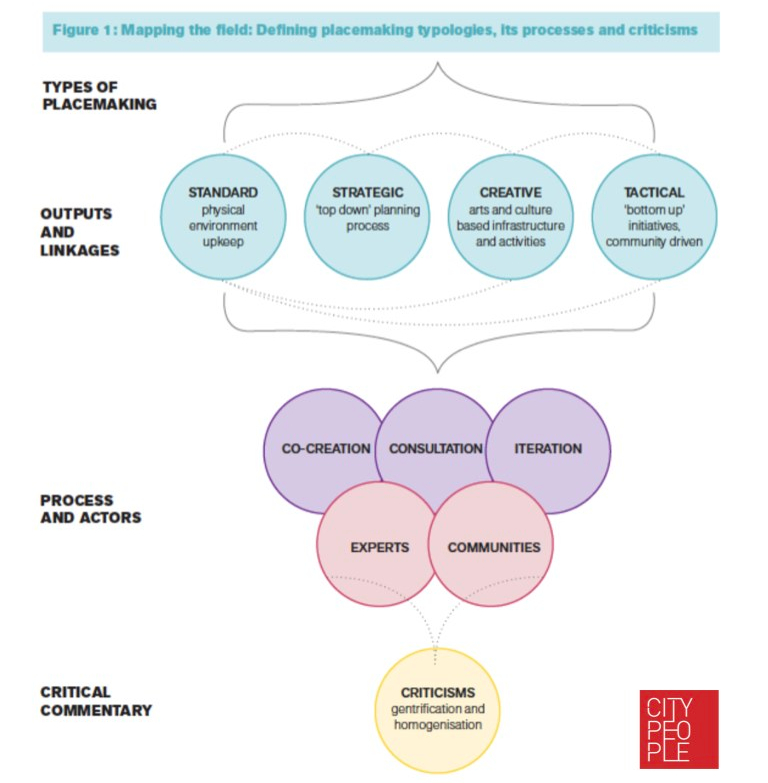

As you can see in the diagramme above, we’ve identified a couple of areas of critique that creative placemaking attracts. On the one hand, some placemaking can sometimes use generic approaches that can produce (somewhat ironically) a sameness of place. On the other hand, : placemaking is often cited as a cause of neighbourhood gentrification.

On the homogenisation front, I’m right there. One of my least favourite parts of a lot of placemaking practice is that it often uses generic tools in an effort to get communities to engage with their places. Grimy parklets with dying trees, colourful chairs poised on astroturf circles, lonely coffee carts and food trucks. Did anyone mention those giant pot plants? These are the easy-reach, and often wheeled out tools of Placemaking 101. They do a job yes. But do they really get people thinking about what is special and particular to their place? I’m not so sure. A better approach to meaningful engagement with place seeks to draw out the specific character of a place: its stories, physical character and its communities. Our Urban Innovation Accelerator is the tool we have devised for just that purpose. Anyway that’s material for another rave…

No doubt, there will be contention that placemaking is a tool for gentrification and a lot of heat under some academic collars. Don’t get me wrong, the dispossession of communities that happens with gentrification is a serious concern and it rightly attracts debate. The jury is still out on whether creative placemaking can be identified as a prime cause on this. But either way, merely measuring the effect of creative placemaking is not a handshake with the devil.

As a research team we identified that the lack of concrete methodology for measuring the value of creative placemaking was an Achilles’ heel to its sustainability. For better or worse, the clearer picture we have of the effects of placemaking the more empowered we are as a community to make good decisions. So that’s the job we’ve undertaken and at the moment we’re refining what sort of indicators might be a good measure for valuing placemaking.

So watch this space for more on that – later this year.

Happily, Lew is the first to admit that these are not neat and tidy compartments and that there is a lot of bleed between different areas. So as a team, we agreed to adopt his framework as the most useful way to think about creative placemaking in relation to other placemaking practices. As I’ve mentioned, placemaking exists in a contested field and no doubt there will be dissent among practitioners about whether this is correct or not. But we believe Lew’s framework lends itself to the diversity of placemaking projects around the world.

Happily, Lew is the first to admit that these are not neat and tidy compartments and that there is a lot of bleed between different areas. So as a team, we agreed to adopt his framework as the most useful way to think about creative placemaking in relation to other placemaking practices. As I’ve mentioned, placemaking exists in a contested field and no doubt there will be dissent among practitioners about whether this is correct or not. But we believe Lew’s framework lends itself to the diversity of placemaking projects around the world.